The Modern Data Lake is a Database

I was recently talking to some coworkers about the mix of data technology we have in our stack. Apache Spark, HDFS, Amazon Athena, Amazon S3, AWS Glue… The list is long. The technologies obviously work together somehow, but to a newcomer it may not be clear how each technology relates to the other. And in the details of how a given technology works it’s easy to lose sight of what purpose it serves in the grand scheme of things.

In a previous post we discussed why many teams use both Postgres and Redshift, or some equivalent, in their data stack. In this post let’s look at the broader collection of data systems that constitute the modern data lake and give you, the newcomer, a mental map of them organized around a longstanding and very useful abstraction—the database.

What is a Database?

First, what is a database? In the abstract, it’s a system for storing and retrieving data. For the purposes of this post, however, I want to take a more practical view inspired by the classic graphical database client interface that is widespread in the software industry.

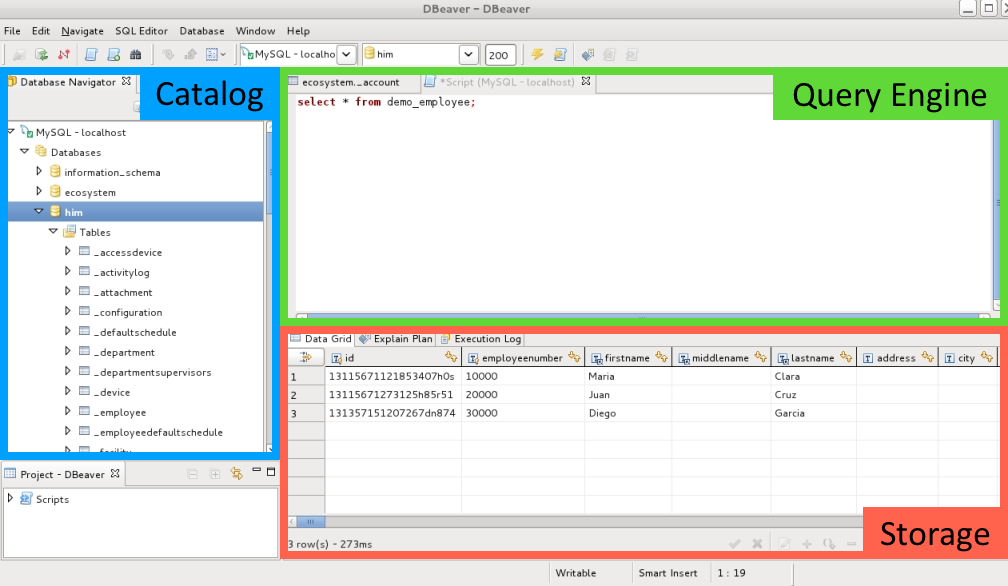

So in practical terms, this is a database:

Specifically, it’s a collection of three components that work together as one system:

- Catalog: The Catalog tracks what data you have – i.e. schemas, tables, and columns – and where in the Storage layer to find it. The Catalog also tracks statistics about the data, like how many rows are in a table, or what the most common values in a specific column are. The Query Engine uses these statistics to figure out how to execute a query efficiently.

- Query Engine: The Query Engine is what takes your query, in this case a SQL query, and translates it into specific machine instructions that will fetch and assemble the data you asked for. In other words, it takes a declarative query describing what you want and translates it into instructions detailing how to get it. The Query Engine uses the Catalog to lookup the datasets referenced in the query and find them in Storage.

- Storage: The Storage layer holds all of the database’s data. Its job is to store all the rows of data for all the tables in the database and retrieve or update them as requested.

Every traditional relational database system, like Postgres or MySQL, comes with all three of these components packaged into one coherent system. They work together seamlessly, but they’re also inseparable. You cannot, for example, query or update the data in the database using regular Unix tools like grep or sed; you have to go through the database’s query engine. And while some databases let you use the database’s query engine to query data from outside of its own storage layer, it’s very much a secondary capability that you wouldn’t want to rely on heavily.

Breaking up the Database

In the years since this formula was first developed and perfected, there’s been an explosion of new database and data processing technology: Graph databases, document databases, column-oriented databases, stream processing systems, and more. Among these new technologies is the group of distributed data processing systems – also known as “Big Data” tools – dominated by the Hadoop ecosystem. This ecosystem includes systems like Apache Spark.

Broadly speaking, what distinguishes these systems from traditional databases is that they enable you to process a) large amounts of data b) in varied formats c) quickly d) and affordably. They do that by distributing the work to process data over a large number of cheap machines that are clustered together, and by allowing you to process data as it is on your storage system. In other words, instead of sending your data to the query engine, you send your query engine to the data. This contrasts with a traditional database system, where you would need to load the data into a specialized format in an area managed exclusively by the database. So to give a simple example of something you could do with these systems, which wasn’t as easy or practical to do before, you could process 20 TB of plain old CSV data distributed across 100 cheap machines in a few minutes.

When these systems were first being developed, the focus was on making them scalable and fault-tolerant, and the programming APIs weren’t very friendly. Over time, these distributed data processing systems evolved to recreate the convenience and productivity of the traditional database system. Instead of MapReduce, you could now query data using plain old SQL. And instead of referring to data by fixed paths on a filesystem, you could now refer to them by abstract schema and table names, just like in a traditional database.

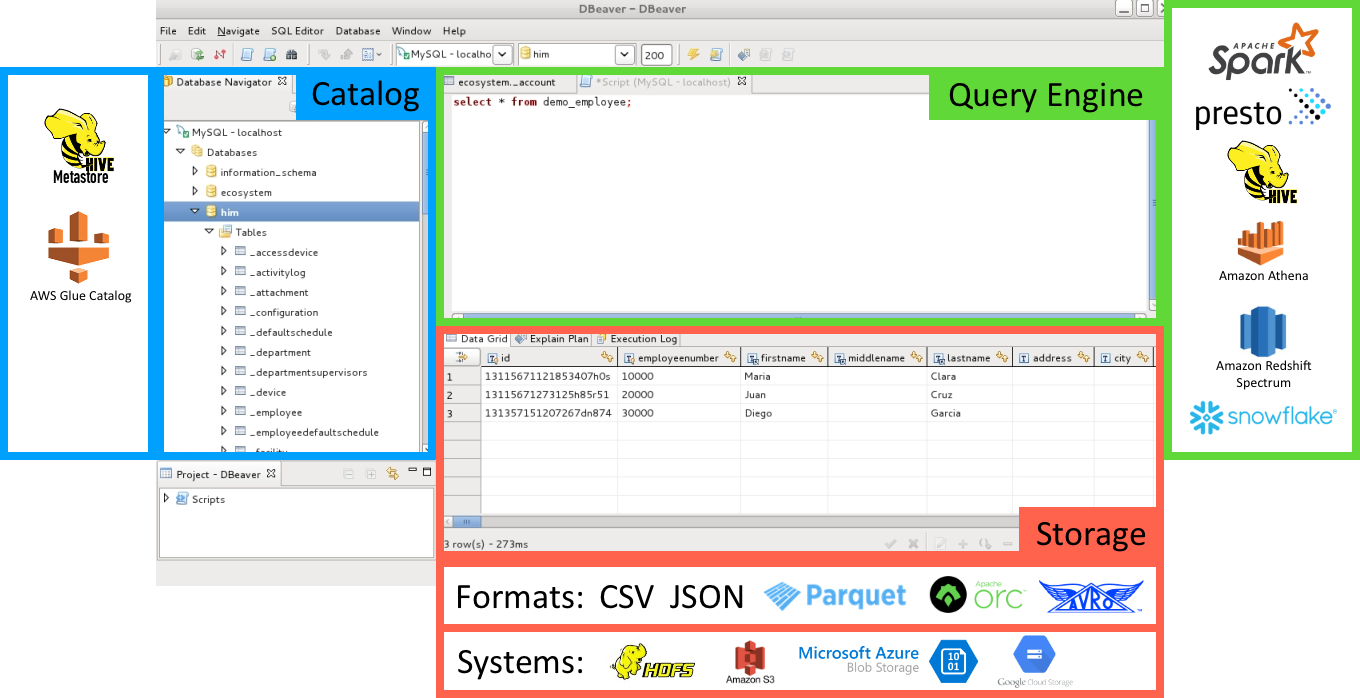

In effect, the people building these systems took the three components of the traditional database – Catalog, Query Engine, and Storage – and reinvented each as a stand-alone component for the distributed, massively scalable world. These components interoperate through shared catalog and storage formats.

This means you can store your data in one place, like S3, and query it using multiple tools, like Spark and Presto. These query engines will have the same view of the available datasets by pointing to a shared instance of the Hive Metastore.

Another key point is that storage is split up into formats and systems. Instead of having your data in a closed format on a single server operated on by a single database system, you can have data in multiple, open formats (like CSV or Parquet), across several storage systems. And because the data formats are not specific to any query engine, data created by one query engine can easily be read by another.

Example: The Spark “Database”

Apache Spark is extremely popular with teams building data lakes. If you’re reading this post, chances are that you’ve used it at some point. But if your experience with Spark was limited to its RDD or DataFrame APIs, you may not have realized that it can be integrated with these other systems to create a logical database with SQL as the primary query language. So let’s take a quick look at how to do that, keeping in mind that you can do something similar for many other “Big Data” query engines.

Spark comes with a command-line utility called spark-sql. It’s similar, for example, to Postgres’s psql. It gives you a SQL-only prompt where you can create, destroy, and query tables in a virtual database. By default, the catalog for this database is stored in a folder called metastore_db, and the data for the tables in the database is stored in a folder called spark-warehouse, typically in Parquet format. That’s already pretty neat, but you can take this further by calling ./sbin/start-thriftserver.sh from the Spark home directory. This will start up a JDBC server that you can connect to with any old database client, like DBeaver. That will give you the full “Spark is a database” experience. I won’t go over how to do this in detail, since that’s not the focus of this post, but the documentation for Spark’s JDBC server and SQL CLI is here.

We can extend this experience to the cloud. If you work with Spark on Amazon EMR, you can connect Spark to the AWS Glue Data Catalog. This gives Spark the same view into your datasets that several other AWS services have, including Amazon Athena and Amazon Redshift Spectrum. In other words, you can have one catalog, managed by AWS Glue, one location for your data, on S3, and any number of different services or query engines updating or querying that data using SQL. And just as you can with Spark running locally, on EMR you can start a JDBC server and connect to it with a regular database client.

Final Thoughts

I hope this post connected some dots for you about the various distributed data systems out there. There are many ways to conceptualize a data lake. Thinking of it as a database – i.e. a combination of catalog, query engine, and storage layer – provides a familiar abstraction that will help you mentally map out many of the technologies in this space.

This idea is more powerful than just as a conceptual tool, though! After all, a team may use these same technologies to build a data lake without integrating them to create that cohesive “database” package. What are they missing out on? As we touched on earlier, by actually building your data lake around the database abstraction, you can can shift the focus of your work away from where the data is or how to manipulate it, and instead focus on what data you want. Let’s explore this idea in a future post.

Thanks to Michelle, Yuna, Cip, and Sophie for reading drafts of this post.