Thoughts on States vs. Transitions

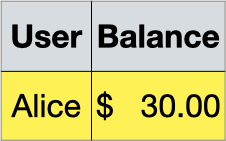

Many years ago, working as a database developer at a video game company, I was tasked with designing the database behind an in-game wallet service. The wallet service would store each player’s current balance and transaction history. In other words, it was a simple banking database.

Working on that problem gave me a hands-on introduction to several recurring themes in software engineering. One of those themes is the divide between two ways of thinking about data: thinking about the state of something, and thinking about the transition of something from one state to another.

The state of something describes what it is at a specific point in time, and a transition describes a change from one state to another—i.e. how the state changed at a particular point in time. There are many other ways to describe the same concepts, but I’ll stick with state and transition for this post. In this player wallet scenario, a player’s balance is a piece of state, whereas the individual transactions that the player makes are transitions on that state.

In this post I’d like to share all the common threads I’ve found in software design and data management once I started to think about this divide.

Perspective: State-First or Transition-First

When you have a problem that requires you to manage both states and transitions, like in the player wallet example, one of those ways of thinking about the problem will tend to dominate. What I’ve noticed is that, whichever way is the primary way you think about the problem, you end up needing to build automatic and efficient ways of deriving the other representation of your problem.

- If states are the primary way you think of a problem, then when a piece of state changes you need to automatically derive the transitions that implement that change.

- If transitions are the primary way you think of a problem, then as the number of transitions grows large you need to build a way to efficiently query the state at a specific point in time (which is typically “right now”).

Our wallet example is a typical example of a “transitions-first” problem. The primary data are the individual transactions against a balance, since that corresponds most naturally to the activity we’re capturing, so we need to build an efficient way to derive the current balance from the history of transactions.

There are many problems that fit this “transitions-first” pattern, as well as problems that fit the “state-first” pattern. Let’s look at some examples of each, and see how in each case the secondary way of thinking about the problem needs to be automatically derived.

State-First Thinking

Infrastructure Management

Terraform is a tool for managing infrastructure that uses declarative configuration files to describe the infrastructure under its control. For example, here is a simple configuration that describes a single EC2 instance running on AWS:

provider "aws" {

profile = "default"

region = "us-east-1"

}

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-00b882ac5193044e4"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

tags = {

Name = "TerraformExample"

Owner = "Nick"

}

}

The configuration doesn’t explain how to create this infrastructure. It simply describes what the infrastructure is. In other words, it describes the state of the infrastructure.

When you deploy this configuration, Terraform compares the desired configuration against what is already out there and automatically figures out what operations are required to change the deployed infrastructure to match the configuration. To use the terminology we’re using in this post: The user specifies the desired infrastructure state, and Terraform automatically derives the required transitions to bring about that state.

So when you first deploy the above configuration against an empty environment (at least to Terraform’s knowledge), Terraform reports what actions it will take to bring about the specified infrastructure:

An execution plan has been generated and is shown below.

Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example will be created

+ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

+ ami = "ami-00b882ac5193044e4"

...

+ tags = {

+ "Name" = "TerraformExample"

+ "Owner" = "Nick"

}

...

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

Suppose that after you deploy this infrastructure, you update your configuration to change the tags on the instance:

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

...

tags = {

Name = "TerraformExample"

Owner = "Bob"

Environment = "Dev"

}

}

When you instruct Terraform to deploy this change, it figures out how to modify the existing infrastructure to match your desired configuration, even though you haven’t specified how it would do that, only what infrastructure you want at the end of the day:

An execution plan has been generated and is shown below.

Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

~ update in-place

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example will be updated in-place

~ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-00b882ac5193044e4"

...

~ tags = {

+ "Environment" = "Dev"

"Name" = "TerraformExample"

~ "Owner" = "Nick" -> "Bob"

}

...

Plan: 0 to add, 1 to change, 0 to destroy.

As you can see in the plan, Terraform detects that only parts of the infrastructure need to be changed, and it figured out exactly how to change them to match the desired state.

As a Terraform user, you think about infrastructure primarily as what you want its current state to be, and Terraform figures out for you how to transition your infrastructure to match your desired configuration.

This seems like a natural way to approach infrastructure management, but you can probably imagine how a transitions-first approach to this problem would play out. Instead of specifying “I want one instance” in your configuration, you’d say “Add one instance”, and so on. You’d then have to carefully run just the appropriate steps as they are needed, or somehow build idempotency into each operation so it’s safe to rerun them without careful pre-planning. Otherwise, you’d likely end up creating duplicate infrastructure or make unwanted changes.

Database Schema Migrations

Relational databases are typically tightly coupled to the applications they back. As an application changes, the database schema backing it often also needs to change. But where an application can be updated with a simple code push, the database needs more care because it’s stateful. In other words, it’s carrying all this data that you want to maintain; you typically don’t want to update your database schema by dropping the whole database and redeploying it from scratch, which is in effect what you do when you deploy a new version of your application—replace the old application code entirely with the new. Instead, you want to migrate the database schema in-place, preserving all the data.

When I worked as a database developer, one of my tasks was to plan and execute migrations like this. I’d compare the current database schema against the new one that needed to be deployed, and hand craft a migration script that would ALTER tables and make any other necessary changes to mutate the schema as needed.

-- Version 1

CREATE TABLE person(

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

first_name VARCHAR(200),

last_name VARCHAR(200)

);

-- Version 2

CREATE TABLE person(

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

first_name VARCHAR(200),

last_name VARCHAR(200),

birth_date DATE

);

-- Derived v1->v2 migration script

ALTER TABLE person

ADD COLUMN birth_date DATE;

Every release of an application had an associated database schema as well as a migration script to upgrade a database from the previous schema version. The full database schema at a given version was the primary description of the database, and the migration script was derived from the comparison of the full schema at two different versions.

To fit this into the common thread I’m tracing in this post, database schemas fit the state-first mode of thinking. The state of your database schema at a given version is primary (i.e. what the schema is), and the transitions from one schema version to another are secondary (i.e. how to get the schema to that state).

There are tools for approaching database schemas in this fashion, like Redgate SQL Compare for SQL Server and OnlineSchemaChange for MySQL. You give these tools two full schemas, and they compute the appropriate migration script. There are some risks to performing automatic migrations in this fashion. There may be semantic changes to your schema or strict availability requirements that an automated schema migration tool cannot satisfy without human input. But I think these tools address the problem of schema migrations in a conceptually natural way.

Source Control: Commits

Consider git. Depending on what you’re doing, git seamlessly moves between a state-first and transition-first view of the world. One of the primary things you do with git is create new commits to capture changes to your codebase. When you create a commit, git derives the diff for the commit by comparing the current state of your codebase against its state at the most recent commit.

diff --git a/.travis.yml b/.travis.yml

index c7938b6..c1a3c91 100644

--- a/.travis.yml

+++ b/.travis.yml

@@ -1,6 +1,5 @@

language: python

python:

- - "3.4"

- "3.5"

- "3.6"

# Work-around for Python 3.7 on Travis CI pulled from here:

In other words, you as the developer focus simply on what you want your code to look like now, and git figures out for you how to capture that as an incremental change from the most recently committed state of the code. You specify the desired state of the code, and git computes the transition from one state of the code to the other.

The derived transitions have a number of uses which you are probably familiar with. We’ll take a look at some of them in the next section.

Transition-First Thinking

In contrast to these examples of state-first thinking, we have transition-first thinking. This form of thinking naturally fits many real-world problems that are oriented around capturing or responding to events: a customer bought something; a user added a comment; a player made a move.

We saw how bank transactions fit this way of thinking; the individual transactions are primary, and the account balance is derived from those transactions. Let’s take a look at a few more examples of transition-first thinking and see how the state of the world ends up being derived from those transitions.

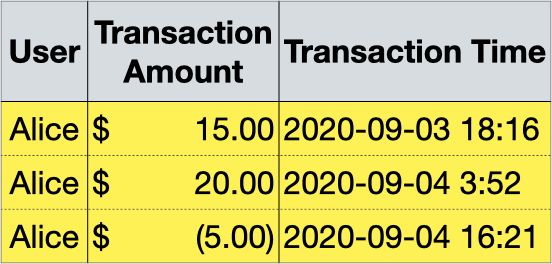

Social Media Activity

“Like, comment, and subscribe!” – a common refrain on social media platforms – also captures a straightforward example of a transition-first problem. Users each add individual likes to a post, for example. Each such action is recorded in the backing database. That’s the primary record of what happened.

When people view a given post, however, they don’t see all the individual likes (at least not by default). What they see is a summary which is derived from all the individual likes and represents the current state of the total. From the perspective of the backend database, the individual likes are primary; the derived total is secondary.

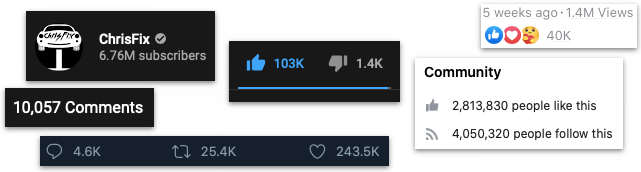

Turn-Based Games

Games like chess are well represented as a sequence of transitions. Each player takes a turn to make a move, and at any point in time the state of the game can be derived from the history of moves that have been made leading up to that point.

These are the first 10 moves of each player in Game 1 of the 1996 match between Garry Kasparov and Deep Blue.

- e4 c5

- c3 d5

- exd5 Qxd5

- d4 Nf6

- Nf3 Bg4

- Be2 e6

- h3 Bh5

- 0-0 Nc6

- Be3 cxd4

- cxd4 Bb4

The state of the board shown in the image is derived from this sequence of moves.

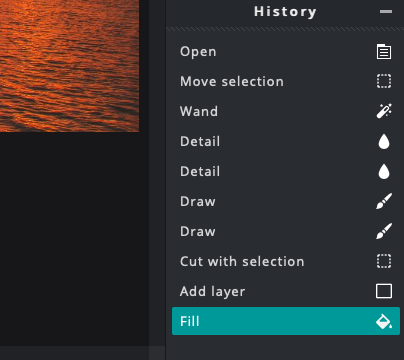

Image Editing

Image editing tools like Photoshop track your edits to the image you are working on, allowing you to easily undo changes or quickly flip between past image states.

You can think of the current state of the image as being derived from the history of edits to the original image. Each edit is a transition from one image state to another. The edits are the primary activity the user engages in, and the resulting image follows from them.

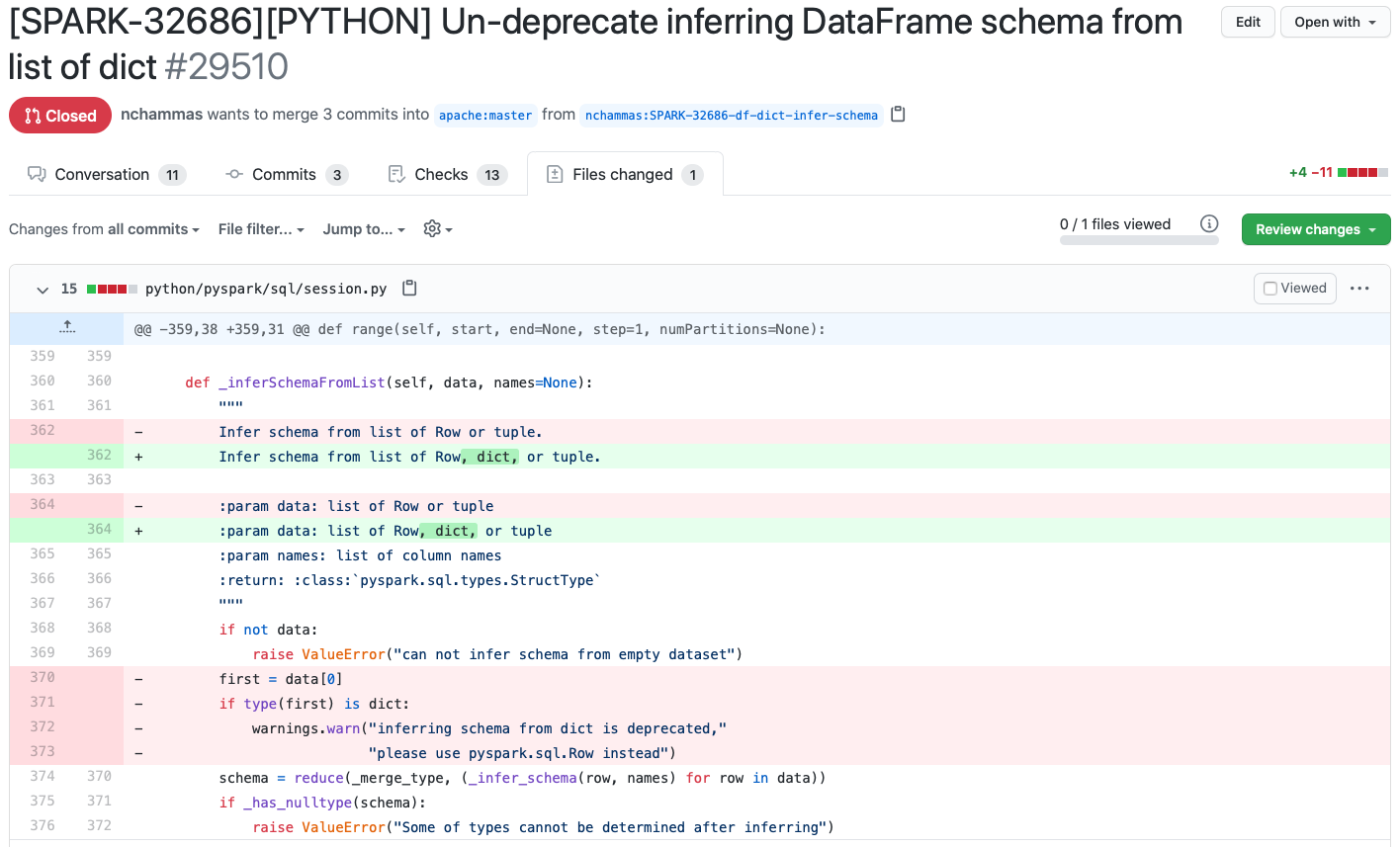

Source Control: Code Review

This is the other side of source control systems like git. Git lets you focus on the state of your code when you make a commit, and derives from that the transition from one state of the code to another. But after that, almost everything else in git starts with the transitions first and derives from those the state of the code.

A great example of a transitions-first interface is what happens when you submit a code change for review, like a GitHub Pull Request.

Instead of presenting the entire code base at once, the pull request focuses on a set of code changes – a “diff” – that a person can review in isolation. Focusing on this limited transformation of the code is what makes code review practical. And when a pull request gets merged in, git uses the encapsulated set of changes to efficiently update all downstream clones of the repository. The diff is primary, and the state of the codebase is derived from a series of transitions (i.e. diffs).

Thanks to Ivan, Michael, and Cip for reading drafts of this post.