A Query Language is also a Data Constraint Language

What’s the difference between a data constraint and a data query? Is there anything that can be expressed in one form but not the other? My sense is that there is no such thing.

A constraint – or, similarly, a validation check1 – is a description of what your data should or shouldn’t look like. A query serves the same purpose. It describes data that has a specific “shape” or satisfies certain properties. Anything that can be thought of as a constraint can also be expressed as a query.

Consider one of SQL’s “built-in” constraints, PRIMARY KEY. It’s such a commonly used constraint that, presumably, SQL’s authors felt it merited a dedicated keyword. But a primary key constraint can also be expressed as a plain query.

-- `PRIMARY KEY` expressed as a plain SQL query.

-- `id` is our primary key column.

SELECT id, COUNT(*) AS id_count

FROM some_table

GROUP BY id

HAVING (

id_count > 1

OR id IS NULL

);

As long as this query returns nothing, our constraint holds. If some data violates our constraint, then this query will return precisely the violating data.

This ability to express constraints as queries isn’t specific to SQL. Any query language can do this. Let’s express this same constraint using Apache Spark’s DataFrame API, which is roughly equivalent to SQL in expressiveness:

# `PRIMARY KEY` expressed using PySpark's DataFrame API.

(

some_table

.groupBy("id")

.count()

.where(

(col("count") > 1)

| col("id").isNull()

)

)

As another quick example, here is FOREIGN KEY expressed as an SQL query:

-- `FOREIGN KEY` expressed as a plain SQL query.

-- book.author_key is a foreign key to author.author_key.

SELECT b.*

FROM

book b

LEFT OUTER JOIN author a

ON b.author_key = a.author_key

WHERE

b.author_key IS NOT NULL

AND a.author_key IS NULL

;

And again using Spark’s DataFrame API:

# `FOREIGN KEY` expressed using PySpark's DataFrame API.

(

book

.join(author, on="author_key", how="left_outer")

.where(book["author_key"].isNotNull())

.where(author["author_key"].isNull())

.select(book["*"])

)

If every row in book points to a valid row in author (or points to no author at all), then these queries return nothing. If a book points to an author not in our author table, then our foreign key constraint has been violated and these queries will return the rows from book that point to a bad author key.

Not Just the Built-In SQL Constraints

My feeling is that any possible constraint or check you can think of can be expressed in this way, using the query languages we are already familiar with. And since we are using mature and well-understood query languages, we can reuse all the constructs and patterns they provide: functions, subqueries, common table expressions, and so on.

To that end, let’s express a more complex constraint as a query, using this example scenario described in Designing Data-Intensive Applications2:

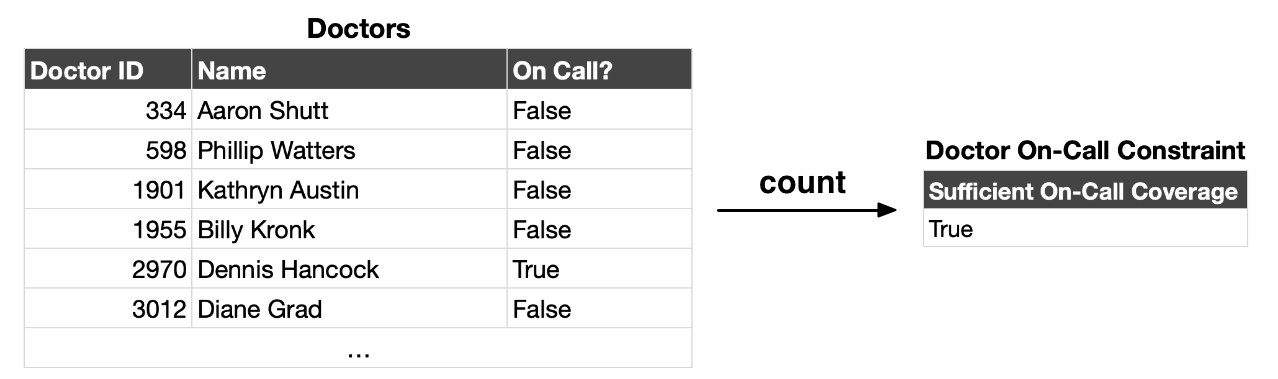

[Y]ou are writing an application for doctors to manage their on-call shifts at a hospital. The hospital usually tries to have several doctors on call at any one time, but it absolutely must have at least one doctor on call.

You can’t express this constraint using any of SQL’s built-in keywords, but it’s pretty straightforward as a query.

-- Doctor on-call constraint expressed as SQL.

SELECT COUNT(*) >= 1 AS sufficient_on_call_coverage

FROM doctors

WHERE on_call;

If we have at least one doctor on-call, then sufficient_on_call_coverage is TRUE, otherwise it’s FALSE. And as before, this constraint can be expressed in another query language like a DataFrame API, not just SQL:

# Doctor on-call constraint expressed using PySpark's DataFrame API.

from pyspark.sql.functions import count

(

doctors

.where(col("on_call"))

# I don't call .count() here but do it instead inside the

# .select() so this query is semantically equivalent to the SQL one.

.select(

(count("*") >= 1).alias("sufficient_on_call_coverage")

)

)

At this point, you can probably imagine any number of arbitrary data constraints expressed as queries. When the constraint holds the query returns TRUE (or, alternately, it returns nothing), and when the constraint is violated the query returns FALSE (or, alternately, it returns the violating data). You can make the query as complicated as you’d like, as long as it fits this pattern.3

Straight from the SQL specification: CREATE ASSERTION

This idea that arbitrary queries can be used to express data constraints is not new. As part of my research for this post I stumbled on a feature of SQL that’s been part of the specification since 1992: CREATE ASSERTION

The idea of SQL assertions is that you can specify constraints on your data via queries that return TRUE when the constraint holds and FALSE when it is violated.

So here’s our primary key constraint re-expressed as an SQL assertion.

CREATE ASSERTION some_table_primary_key

CHECK (

NOT EXISTS (

SELECT id, COUNT(*) AS id_count

FROM some_table

GROUP BY id

HAVING (

id_count > 1

OR id IS NULL

)

)

);

If some_table should ever come to have more than one row with the same id, or a row with a NULL id, then the inner SELECT will return some results, causing the NOT EXISTS check to return FALSE, thus violating our some_table_primary_key constraint.

Here’s the doctor on-call constraint expressed as an SQL assertion.

CREATE ASSERTION sufficient_on_call_coverage

CHECK (

(

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM doctors

WHERE on_call

) >= 1

);

Any constraint you can express as an SQL query can be tweaked to fit this form of an ASSERTION. Popular DataFrame APIs like Spark’s don’t offer assertions, but we could easily imagine a couple of potential DataFrame equivalents to SQL assertions. Here, again, is the on-call doctors assertion:

from pyspark.sql.functions import count

# Hypothetical DataFrame Assertion API, inspired by Spark's

# `DataFrame.createGlobalTempView()`.

(

doctors

.where(col("on_call"))

.select(count("*") >= 1)

.createAssertion("sufficient_on_call_coverage")

)

# Another hypothentical DataFrame Assertion API, inspired by the Delta

# Live Tables API.

@assertion

def sufficient_on_call_coverage():

return (

doctors

.where(col("on_call"))

.select(count("*") >= 1)

)

Efficiently Checking Assertions

CREATE ASSERTION is, unfortunately, vaporware—no popular database supports it.4 Why is that? There probably isn’t a definitive answer to this question, but we can take some educated guesses at the reasons.

First, generic assertions are not a critical feature. The other constraints SQL supports – PRIMARY KEY, FOREIGN KEY, CHECK – cover most applications’ practical needs. Anything more complex that would need to be expressed as an assertion can instead be implemented in your application layer or as part of a stored procedure.

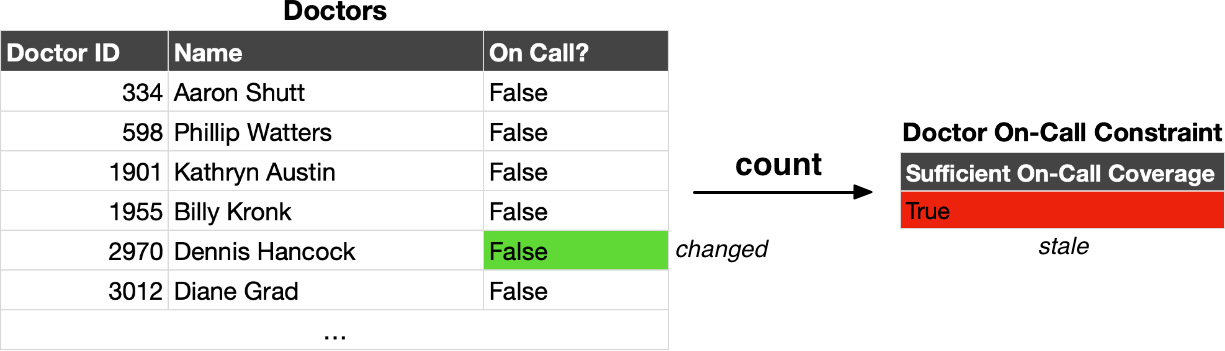

A deeper reason is that assertions are very difficult to check efficiently. An assertion can touch an arbitrary number of tables and involve potentially expensive operations. Every time a table referenced in an assertion is modified, the assertion needs to be rechecked. That means running a potentially expensive query that may involve joins or aggregations to confirm the assertion still holds. While the assertion is being checked, potentially large ranges of data may need to be locked to ensure consistency in the face of concurrent readers and writers. And if the assertion fails, the original modification to the referenced tables needs to also fail and be rolled back. Compare this to the traditional constraints supported by SQL, which are typically limited to the rows being updated and do not require looking outside of that narrow range.

To express this problem differently, a key aspect of what makes assertions expensive to check is that they are expensive to maintain. That is, given a database in a consistent state with some active assertions, how do you check that an assertion still holds when an arbitrary change is made to the database? Naively, this means running the query that defines the assertion. If the query involves a join and aggregation across two large tables, that means computing the join and aggregation against those large tables from scratch. In the case of our doctors example, that means scanning the table to count how many doctors are on-call.

But why should we run anything from scratch? Given an incremental update to our database, we’d ideally want to be able to incrementally update the queries that define our assertions. That is, instead of recomputing the output of an assertion query from scratch, we want to incrementally update the output given the incremental changes to the input tables referenced in the query. So if one doctor updates their on-call status, we should be able to recompute the on-call constraint by looking at that one changed row.

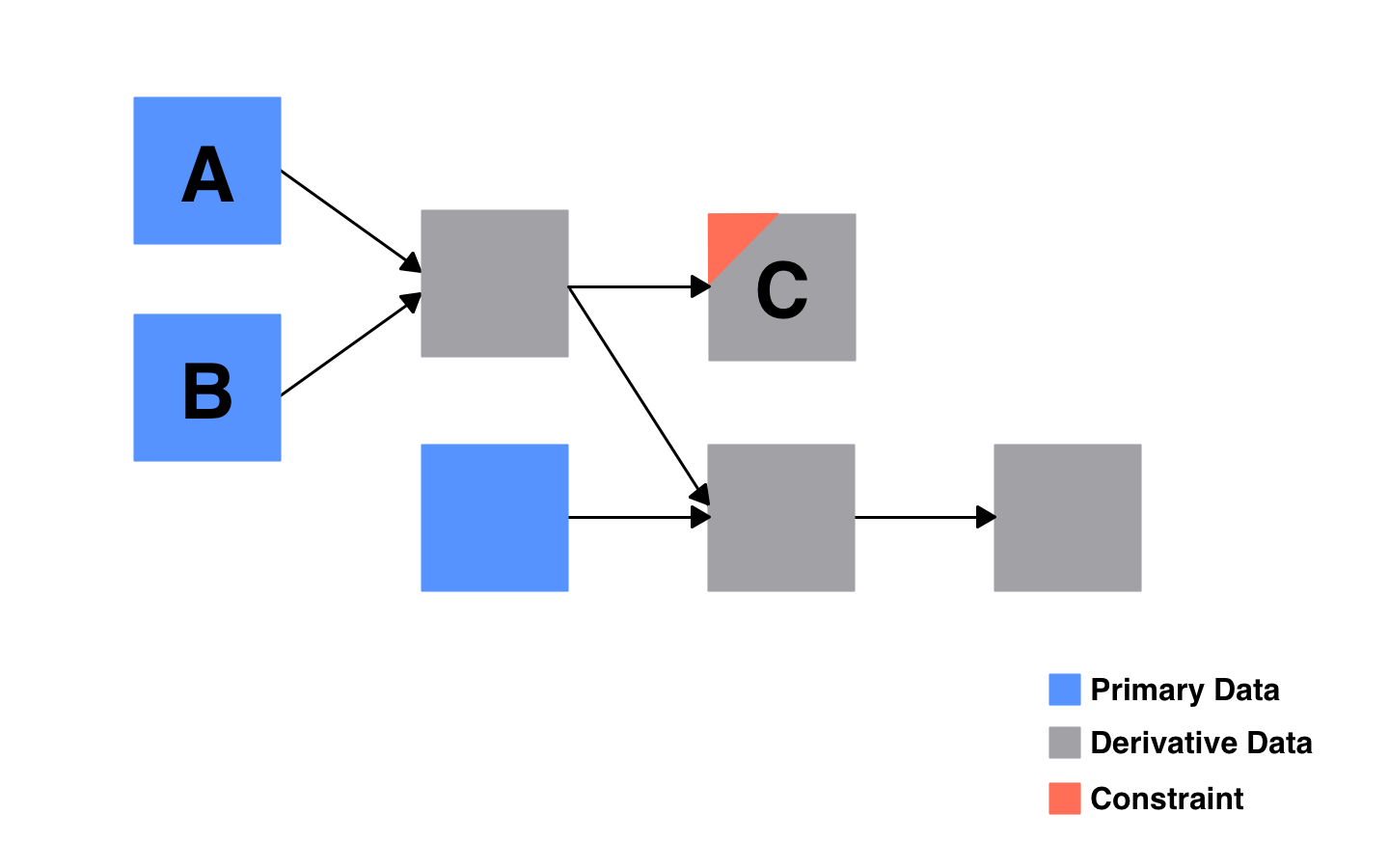

This problem is starting to look like incrementally maintaining a materialized view. To recap how we got here: A general data assertion or constraint can be modeled as a query with a name. A named query is a view. We need to persist the output of this view in order to check it quickly, meaning we need a materialized view. And when the view output changes, we want a way to efficiently update it without recomputing the whole view. So we conclude that – in its essence – maintaining a data constraint is the same problem as maintaining a materialized view.

So what?

So data constraints can be modeled as queries, and efficiently checking arbitrary constraints is the same problem as efficiently updating a materialized view. What does that get us? If nothing else, understanding how these seemingly separate ideas are deeply connected provides some mental clarity.

I find that valuable for its own sake, but there are perhaps some practical benefits we can derive from this understanding, too. The main one being: If your data must conform to some constraints or invariants – that is, things that must always be true (like, there must always be at least one on-call doctor) – then express them declaratively. That could be in SQL, some DataFrame API, Datalog, or something else.

Your data platform may not support realtime enforcement of complex constraints, but you can still periodically check for constraint violations using these expressive, high-level queries written in a declarative language. Declarative checks like this would be much easier to write, understand, and maintain compared to relatively low-level, imperative data tests. And you can run them against your real production data to find problems, not just against test data.

There already are modern systems for applying constraints or validation checks to data lakes, like Deequ and Great Expectations. These systems offer their own custom APIs for expressing checks, instead of building on widespread query languages like SQL or DataFrames. I feel this is a missed opportunity. On the other hand, I suspect at least one benefit they have derived from building custom APIs is to make it easier to compute groups of validation checks efficiently, e.g. by avoiding repeated scans of the same data that may be referenced by multiple constraints.

Other projects that are already based on building graphs of declarative queries – like dbt, Materialize, ksqlDB, and Delta Live Tables – could likewise take advantage of the idea laid out in this post. Some of these projects already allow users to define row-level constraints on a dataset, analogous to the typical SQL CHECK constraint. But what if you could declare the whole dataset itself to be a constraint? Whenever an update to the pipeline triggers a refresh of the dataset, the constraint is rechecked.

Wrapping Up

Model your data platform as a database. Use a declarative query language to interact with it. If you do both of these things, you can then use that same language to define the constraints on your data platform. That’s the message of this post.

This idea is not new. Many teams run their data platform on a traditional relational database where this idea fits most naturally. In fact, Oracle admins have literally been able to implement complex constraints as materialized views – perhaps the most direct application of this post’s idea – since the early 2000s.

But you don’t have to be running on an actual relational database to take inspiration from this idea. Declarative query languages have stood the test of time and been reimplemented for the modern data lake. You can use them today to describe your data in ways that a simple CHECK constraint cannot capture. And hopefully, in the near future we will see more direct support for efficiently maintained, general data constraints.

Thanks to Matthew for reading a draft of this post.

-

The difference being that constraints prevent rule violations upfront, while validation checks identify violations after they have happened. ↩

-

Martin Kleppmann, Designing Data-Intensive Applications, Chapter 7: Transactions, “Write Skew and Phantoms”, p.246-247 in the fourth release of the first edition. ↩

-

Constraints that make use of non-deterministic functions like

CURRENT_TIMEpresent added complications that I won’t get into in this post. But they matter especially when we consider how to efficiently maintain constraints. ↩ -

A user posting to a PostgreSQL mailing list back in 2006 reported that a database called Rdb supported assertions. But I cannot find mention of assertions in the Rdb 7.3 SQL reference manual, which was released in late 2018 by Oracle. ↩